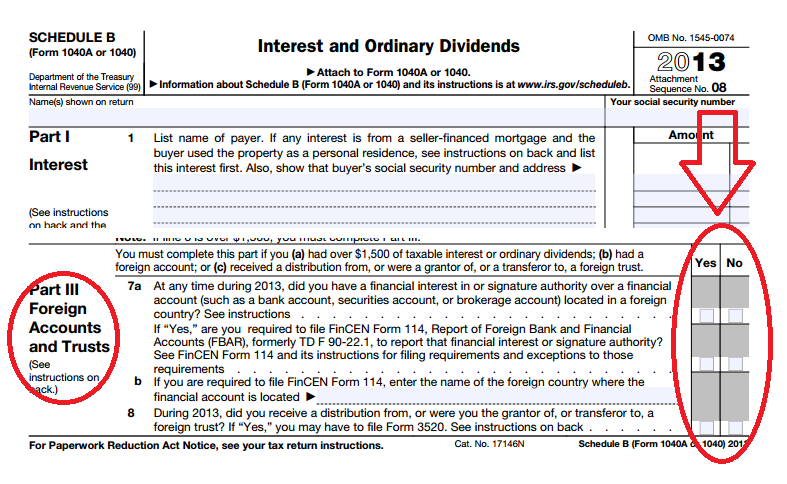

If you have over $10,000 USD in a foreign bank account, you are required to report it to the Internal Revenue Service.

The IRS changed how FBARs are filed. It’s now done online instead of mailing a paper form to Detriot. Here’s a step by step guide to help you through it.

Now before you start, I get a lot of questions from people asking if they even need to file an FBAR. Here’s a link to the IRS website that compares whether you need to file an FBAR or a form 8938. I like this comparison list better than most of the documents about whether you need to file or not. It’s easier to understand in my book. So if you’re unsure, look here before you file: http://www.irs.gov/Businesses/Comparison-of-Form-8938-and-FBAR-Requirements

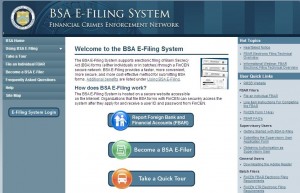

The first thing is to find the website page. Here’s the link: http://bsaefiling.fincen.treas.gov/main.html

When you open the page it says BSA E-Filing System, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. If you’re a normal human being, and you see the “financial crimes enforcement network” you’re going to think you’re in the wrong place! You’re at the right page. And no, you’re not a criminal. By some weird luck of the draw, the financial crimes division is in charge of FBAR filing. Personally I think they should change the name but the IRS isn’t taking my suggestion on that.

As an individual, you’re going to want to select the top box, Report Foreign Bank Accounts (FBAR).

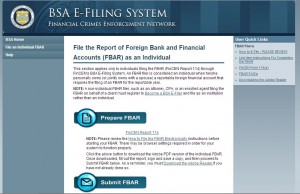

This will take you to the next screen where you can choose whether to prepare or submit your FBAR. We’ll start with preparing.

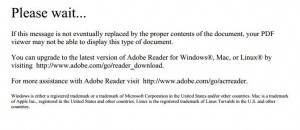

When you click on the “Prepare FBAR” link, you should get a download of the input document. But, you might get this instead:

If your download doesn’t convert from the “please wait” page, you’ll probably have to download a newer version of Adobe reader.

If your download doesn’t convert from the “please wait” page, you’ll probably have to download a newer version of Adobe reader.

[Geeky technical issue: my computer had real problems opening this file. I got around it by downloading the NFFBAR to my computer and then opening the file from there. This might work for you if you’re also having trouble.]

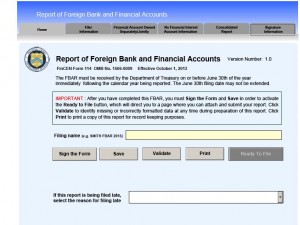

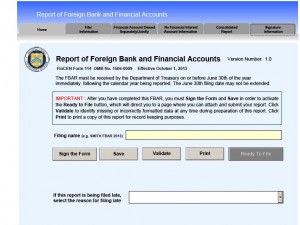

The screen you want to see looks like this:

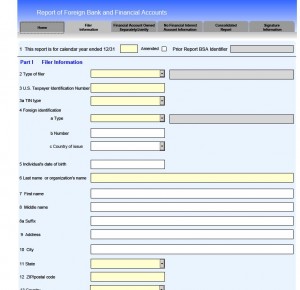

The first thing you’re going to do is name your file so that you can find it again. I’m choosing Roberg FBAR 2013. Next, you’re going to click on the Filer Information tab. You’ll see a screen like this:

That’s going to have all of your personal information, your name, social security number and address. If you don’t have a social security number or ITIN number, then you can use your foreign identification such as a passport number. When you’re done with this section, go to the next tab: Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts.

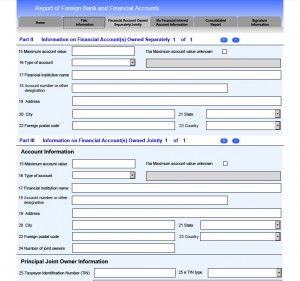

That’s the meat of the reporting form. This is where you put your bank account numbers, the maximum value of your accounts and where they are located. These are accounts that you actually own either by yourself or jointly with your spouse.

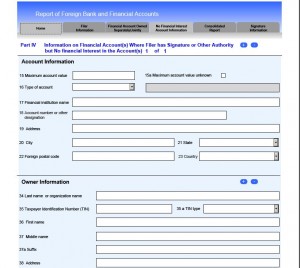

For accounts that you only have a signature authority over, that’s on the next page. It is as follows:

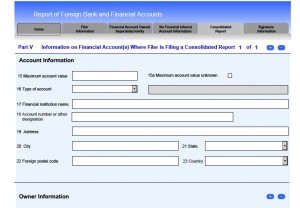

Now this looks pretty similar to the “consolidated account” form as well:

So just make sure you’re on the right screen when you’re filling out the form.

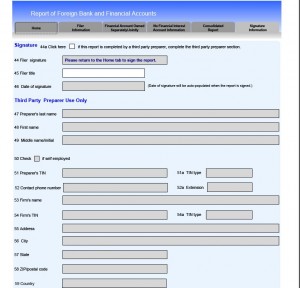

The last page is for the signature date – or, if your tax preparer is doing this for you, that’s the part that she fills out. If you’re doing this yourself, you don’t need to fill out the title on a personal account and the signature date will auto populate when you put the signature on the front page.

Once you’re done, you’re going to go back to the original screen.

Before you actually hit the signature button, you’ll want to hit the validate button. It will check for errors and omissions for you to correct. Then you’ll want to sign the form and save it. Be sure to print your form, and then when you’re all set click on the ready to file button.

That will put you into a final screen where you’re going to put your email address so you can receive confirmation about your filing. After you submit, you’ll receive a confirmation notice. Later, you should receive an email saying that the BSA has accepted the FBAR.

You want to get your FBAR filed by April 15th. The old date used to be June 30th, but the IRS changed that back in 2016. For those of you who are filing back FBARS, you’ll need to answer the question about why you’re late. If you’re filing on time, just leave that box blank.