This is one of those questions I hear all the time: Why do I have to pay tax on my cancelled debt? It’s not income so why am I being hit with income tax?

Here’s the situation—you’ve rung up some credit card bills and then you couldn’t afford to pay them off. You make a deal with the credit card company (or more likely a debt collector) and you agree to pay half of it and they cancel the rest of the debt. Sounds like a pretty sweet deal doesn’t it?

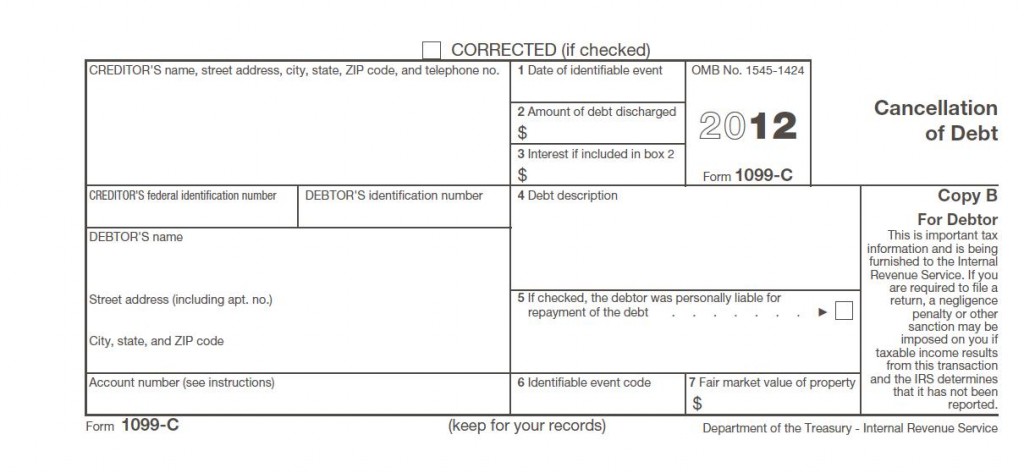

At least it sounds like a sweet deal until tax time. What happens then is that you get a statement called a 1099C form which shows that your debt was cancelled and it becomes taxable income to you. Not so sweet.

But why does it count as income? This one’s easier to explain with an example. Let’s say you charged $20,000 worth of stuff. Let’s say you bought shoes, clothes, a big screen TV and some furniture all on credit. Or maybe you charged medical bills and food. It doesn’t matter what you did to acquire the debt. The results are the same. Then let’s say you lost your job and couldn’t pay for it. The credit card company charges interest on the amounts not paid and the bill goes up to $23,000. You’re in over your head so you get some help from a credit card counselor. With a loan from your parents you settle the bill for $13,000. Now you’re free and clear of the debt.

But tax time comes and you get a 1099C stating that you have income of $10,000 which is the amount of your credit card debt that the credit card company forgave.

It’s counted as income, because unlike your parents, the credit card company didn’t make it a gift. For the credit card company, if they write off your debt, it’s a business expense, and that makes it a deductible business expense to them. If they were to just give you a gift, that’s not a deductible business expense.

You might be thinking that it’s not fair—but in reality, it’s not only fair, but it’s absolutely necessary. You see, the credit card company has to report what you charged as income. Let’s take that TV as an example. You charge $1,000 for the TV and the credit card company is required to pay $1,000 to the store. They record the $1,000 as income to the credit card company and then they expense the $1,000 they paid to the store—they haven’t gotten the $1000 from you yet, but since you’re going to pay it, they report the income. It’s called accrual basis accounting.

But now you’re not going to pay them. They’re already out the $1,000 they paid to the store for your TV and now they’re not going to get the money that they’ve already had to pay their income tax on. So when they get to the point that they’re going to cancel your debt—well they have to issue you the 1099C to prove they cancelled the debt and claim their tax deduction.

But why do they add the interest into it? Once again, they already counted the interest that you should have been paying on that debt as income.

Remember, it takes money to pay for things you want and need. We pay for those things with our income. Usually we think of income as wages, but if we buy stuff and then don’t pay for it, that’s also a kind of income to us as well.

For more information on cancellation of debt, see my blog post titled How to Report Debt Forgiveness (1099C) on Your Tax Return.