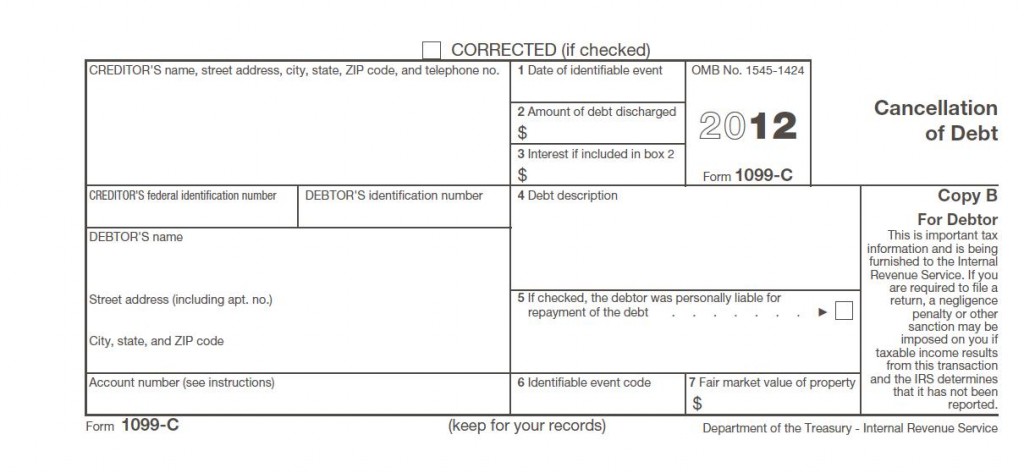

In my last post I wrote about why debt forgiveness counts as income, but I didn’t explain how to report it on your tax return. And it’s important that you do report it, or you’ll be getting a nice little letter from the IRS asking you why you didn’t.

First and foremost, if you received a 1099C for cancellation of debt on mortgage interest, you should be reading a different post. See: http://robergtaxsolutions.com/2011/11/what-you-need-to-know-if-your-mortgage-debt-is-forgiven/ What I’m talking about here is cancellation of credit card debt. It doesn’t get treated in exactly the same way as mortgage interest.

Generally, if you receive a 1099C statement, I think you should see a tax professional—and make sure it’s someone who’s worked on debt cancellation issues before. Not everybody does that. I once had a client who had called around and I was the 5th person he called before he found someone with debt cancellation experience. He had started at one of those big box tax places and was told that he owed the IRS $14,000. That’s when he started thinking he wanted a second opinion. When I did the return, he actually had a refund.

To be fair, his case was unusual and he managed to catch all the breaks in the tax code—but if he didn’t have someone who knew the tax code and where the breaks were—well then he would have been paying $14,000 in income taxes that he didn’t really owe.

So how do you report income from cancellation of debt? Basically, it goes on line 21 of your tax return, in the other income category. It gets taxed just like anything else that goes on that line—at your regular income tax rate. That’s what happened with the $14,000 fellow—his preparer put his 1099C income on line 21. While that’s the correct way to report 1099C income, she had neglected to look for exceptions to see if some (or all) of it might not be taxable.

The two most common exceptions to having your 1099C income being taxed are bankruptcy and insolvency. In bankruptcy, you’ve actually filed for bankruptcy and your case is either under the jurisdiction of the court and the court has granted a discharge of indebtedness—or is under a plan approved by the court. Bottom line—you’ve got the legal paperwork to back up your claim that you should be exempt from tax on your cancelled debt.

With insolvency—it means that your liabilities exceeded the fair market value of your assets immediately before the discharge. Okay, in English. Let’s say you owed $10,000 on a credit card—that’s a liability. Your assets included a car, some clothes, a TV, a little cash in the bank that the value of all that totaled $7,000. Since your liabilities (the $10,000) are more than your assets (the $7,000) you are insolvent by $3,000. So if the credit card company discharged $5,000 of your debt, you would be able to exclude $3,000 from tax but you’d still pay tax on the $2,000 that you weren’t insolvent on.

To report an exclusion of cancelled debt from taxes, you’ll need to use Form 982. Here’s a link to that: http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f982.pdf

If you think you might qualify for the insolvency exclusion, you’ll want to fill out the worksheet located in publication 4681, it’s on page 6. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p4681.pdf

Now to be perfectly honest, I’ve really oversimplified this for the sake of brevity. Many people will have cancelled debt and won’t qualify for any tax forgiveness. Also, it’s important that you don’t file for tax exclusions if you don’t qualify for them (it’s a type of fraud—you don’t want to go there.) And it’s quite possible that you can do everything right with the 982 form and you’ll still get a letter from the IRS asking you to confirm something. (That actually happens quite often so don’t be surprised—it’s pretty normal.)

There are two really important issues you need to learn from this blog post:

- 1099C income must be reported on your tax return

- You may qualify for some type of exclusion so that some (or maybe even all) of it won’t be taxable